In this case, mine was a lonely heart searching for a biscuit recipe. More specifically, the biscuit recipe. Some explanation is required. I have always loved Carson McCullers’ writing, particularly The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. Long before I’d ever been to the South, the early morning scene in the book–where Mick takes a cold biscuit for her breakfast–fired my imagination. Good books do that.

I pictured myself getting up on a summer morning in some southern state, wandering to the kitchen, pouring a cup of coffee and rummaging in the breadbox for yesterday’s biscuit, then sitting on a veranda (large, old, slightly shabby house with trailing wisteria vine), and listening to the birds heralding the day. Perhaps another early riser walking by would say something to the effect of, “Going to be a scorcher today,” and I’d nod wisely.

Such is the scenario the book suggested to me. Now, I am more or less living in the South (depending on where you draw the northern border) and have been defeated consistently in trying to produce a passable biscuit. My efforts usually result in flat, dense disks that resemble hardtack.

When I wrote my novel, Nothing’s Ever Right or Wrong, and wanted to represent a young woman on a rundown farm, with limited means and no handy artisan bakery down the street (let alone in the nearby small town), I had her baking biscuits–a lot of biscuits.

Last fall, I was doing a workshop on editing, called The Soap on the Rope Mistake. It wasn’t a grammar/spelling/punctuation workshop, but rather one on avoiding common pitfalls in our manuscripts. While discussing the importance of keeping our own habits, desires, and proclivities separate from those of our characters, I explained that although I had Stella baking biscuits on numerous occasions, it was natural to her situation. I assured my audience that it definitely wasn’t me; I couldn’t make a decent biscuit if my life truly depended on it.

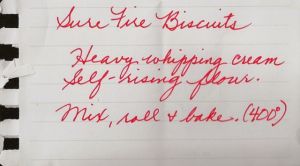

Around fifty people were in attendance at the workshop, many of them authors. I talked with a half dozen after the presentation. One woman, waiting patiently, handing me a slip of paper with the simplest biscuit recipe I ever seen, and told me I didn’t have to go through life biscuit challenged.

I thanked her, put the slip in the notebook, and forgot about it. This spring, I did another workshop, this time on memoir, and discovered the same woman was present. She asked if I’d ever made the recipe and I told her, “Not yet, but I will.” This morning, I tried it. To my astonishment, I made a pan of perfect biscuits that tasted as good as they looked.

What does this have to do with writing? In writing, as in other endeavors, it pays to keep an open mind when we are offered suggestions that might improve our work. Sounds simple, but sometimes, when we believe we know what we are doing, and have a tender writer’s ego at stake, we dismiss–even occasionally resent as interference–the guidance that is offered to us. In working to overcome my occasional resistance to advice, I’ve learned:

1) The people who offers constructive criticism, advice, or insight don’t have to be fellow writers or literary critics; they can be bricklayers, nurses, farmers or stockbrokers. They can be any age, gender, religion, culture, or political leaning. They can be highly educated or marginally literate. Whoever they are, they know about things that we don’t; they’ve lived moment we never will; they’ve experience emotions that are foreign to us; they have something to say and, if we intend to write about their world, we better listen.

2) If other writers offer to read or edit your book, don’t be surprised if they to give in to the urge to rewrite phrases, sentences, even paragraphs. It’s an occupational quirk. Before becoming irate that someone is tampering with your precious words, make a cup of tea and regain your objectivity. Maybe they are right? Maybe they do see a more succinct or dynamic way to convey an idea. Maybe not, but consider the possibility.

3) Don’t shoot the messenger. If your manuscript is returned to you bleeding red ink (think intensive proofread), and you find out you violated one of the common rules of punctuation, grammar, or syntax, curb your impulse to scream, curse the copy editor, or go into deep denial.

It happens–even when we know the “rules” but, for some reason, have developed a mental block to the point that, no matter how many times we’ve done our own proofread, the errors have remained undetected. At this point, you may need something stronger than tea to regain your objectivity. Thank your editing friend and fix the errors. Your hurt pride may take a bit longer, but it’ll heal and you’ll be grateful in the long run.

And me? Tomorrow morning, with temperatures in the high 90s, I will pour a cup of coffee, rummage in my cupboard for a day-old, cold biscuit, sit out on my deck, and salute all my reading friends, copy editors, Mick, Carson McCullers, and the woman you passed me that magic slip of paper.